Recovering from a Colosseum mistake

On worst mistakes and the gladiatorial fight to turn them around

Can mistakes in a fight turn tables?

Hi, everyone-

We live in the age of mistakes.

Like hitting publish and then seeing a typo on the top of the page (definitely happens to me).

But my former professor, Peter Eisenman, one of the iconic New York Five architects, used to tell me that …

Thalia, mistakes make a master.

Truthfully, I thought: “If this is another ‘failing forward’ slogan, I’m out.”

I always felt that he and the rest of the big-wig faculty always spoke in riddles. I didn’t get what he meant!

It’s hard enough to see how they always show up in all-black. Always complete with black-rimmed glasses. With maybe just a hint of white on their collar. Somehow, they’re also always armed with a white paper cup of something hot. Coffee, probably. But maybe also: black-and-white snobbery?

Without going into a whole critique of the pundits’ fashion and word-choice—I should probably say that I would never have had the guts to say any of this to Peter when I was his student.

No way!

Peter might always be that Jewish kid from New York trying to break the walls of presumption. But whenever he’s in front of the room, you could barely tell. Because, when he explains something in an auditorium, he might as well be the first gladiator to ever walk over the dead in the Colosseum.

Walking into a roomful of anything usually makes me feel like an ant under a boot. Walking into the Colosseum when it first opened—I can’t imagine which you’d notice first: the glare of Rome’s most revered on the front row, or the ear-splitting roar of those seated in the upper nosebleed seats.

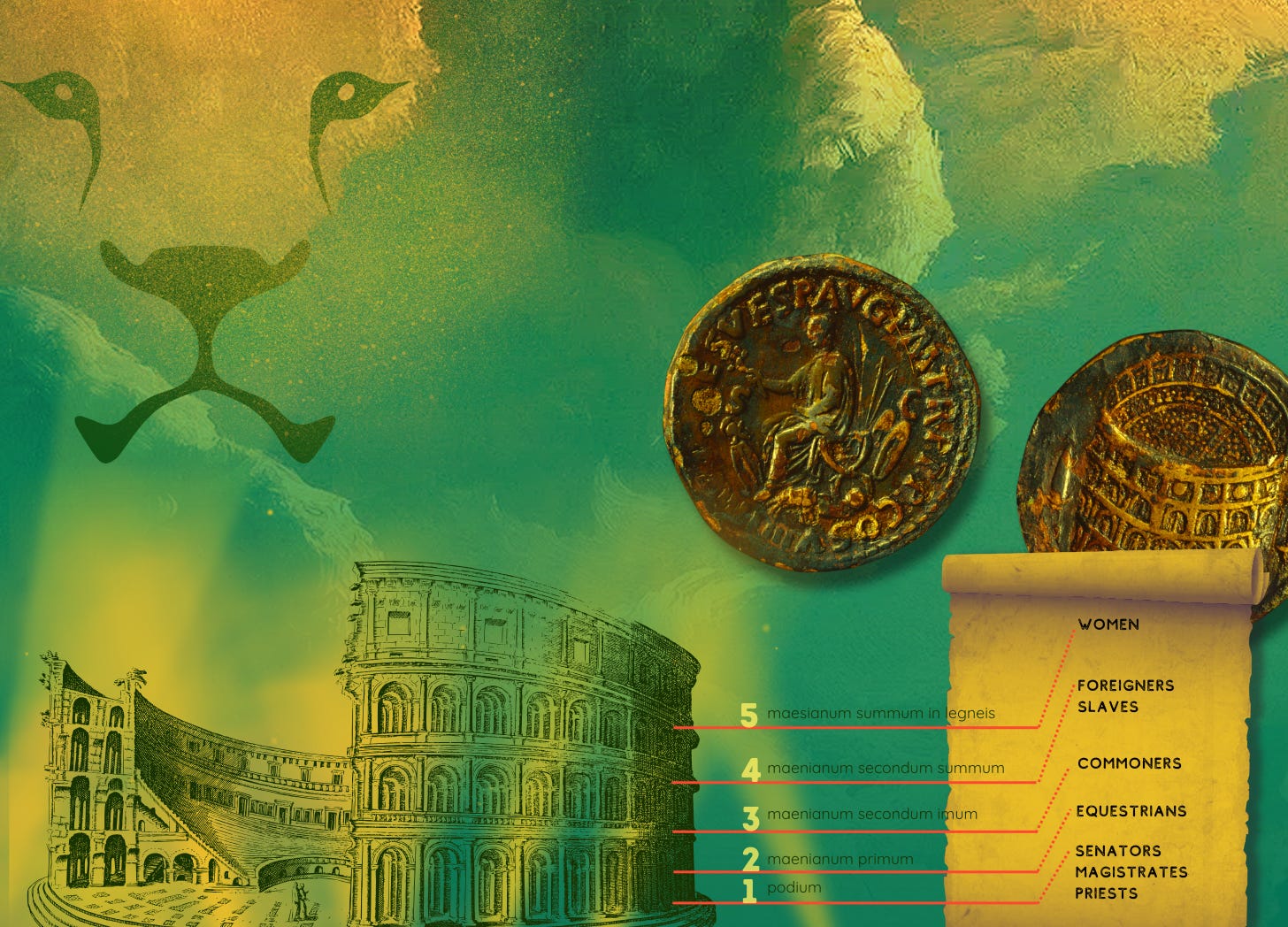

If you look at this studio-recreation of the Colosseum seats, it’s interesting (and disturbing) to realize that free admission doesn’t mean the ability to sit just about anywhere.

But back to Peter for a minute.

To get into his class, I was told that I’d have to register for it first thing at the beginning of the year. So I waited in line on registration day (nothing was online then). I was probably one of the first few in a row of lines set in alphabetical order. I thought: My chances are pretty good! In front of me, a guy just walked away looking a bit put out. When I inquired about Peter’ class—I now understood why he walked away dejected.

Peter’s class … was already full!

Within just minutes.

What on earth!? Is this guy for real?

In the next several days, I had to meet up with this and that dean and professors. To persuade them that I needed to be in that class. I felt dirty. Like I was haggling with a scalper. The department head must’ve felt sorry for me when I started begging. According to him: Peter only takes twenty-five students. So miraculously, I became the twenty-sixth.

I was a young twenty-something then. So, of course, I was begrudging the ridiculousness of having to fight to even hear someone speak! But all that became background noise when I saw Peter.

He was stoutly. He definitely doesn’t have the Renaissance body you’d see in ancient sculptures (Sorry, Peter!) Which I guess was what I was foolishly imagining when I think of a superstar of any field.

Peter looked more like a bull-dog than a bull-fighter. With that quiet face that calls all bull. And that steely forehead lines, like that of a bullet.

Before he opened his mouth—he might as well be an absolute emperor.

When he first opened his mouth—he became the immortal gladiator.

I can’t tell which of the two is more frightening. And my internal battle in picking a side of him I prefer, is itself … frightening.

Peter the Emperor doesn’t move. Peter the Gladiator, however, moves his words like light. Sometimes harsh. Sometimes warm. Sweating once. Salivating twice. He was comfortable with discomfort. Sometimes, I’d catch him pausing after his own words. As if searching for wisdom—not yet realized.

It’s like he knew:

Words are armors in the lands of immortality.

Immortality, of course, is a fool’s dream.

Especially when one is the star-teacher at the center of an auditorium. Or when one is a gladiator in the Colosseum. A live bait for those watching. Waiting breathlessly in defense of greatness. Or in want of a great fall.

I’ve written about this in a number of other amphitheater-focused pieces, like:

In ancient Rome, though, gladiators weren’t necessarily matched by size. Not like all the sports leagues you see today—where the heavyweights never butt heads with the lightweights. Rather, in the Colosseum, a net-and-trident wielder (retiarus) would often be matched against a heavy-armor fighter (secutor). The thinking is that:

Philosophies will never be timeless unless their worth is first tool-tested in battle against—and here’s the interesting part—their next of kin.

When Peter stood in front of our class, he knew us twenty six by name. We would sit in the front row. And yet, people who aren’t enrolled, would somehow manage to turn up and stand along the back-wall. Every time! Sometimes, they’d far outnumber the twenty-six.

Felt a bit more like a fight than a class.

He didn’t know these people. I guess like a gladiator, he wouldn’t know the audience that often operates on impromptu.

He definitely didn’t know the nosebleed student who showed up all the way in the back, folded his arms in front of his chest, and waited to see what the fuss was all about.

Peter most definitely didn’t know, not with certainty anyhow, that a barely-twenty-something kid who wasn’t even enrolled in his class, would raise his hand and persist to keep it there … until he was called to speak.

The smell of a challenge is the sweat of a seafaring beloved who returned—an enemy. The air is just not the same.

And it isn’t just the reigning champion who can smell this. The auditorium can, too. There’s something different about this raised hand.

It makes the challenge … steamier.

Peter’s not new to hecklers. He’s not new to young guns trying to muscle out the old. He’s not even new to arguments meant to shake the status quo. After all, it is about at this point in a gladiatorial fight that the event organizers (editores) would make mid-play changes. To keep the nosebleed crowd blood-thirsty. To keep the rich ticket-holders brain-hungry. And to keep the rest with the question of:

Should we keep faith with our champion? Or should we back the steam of the underdog?

Besides, we, the people, want to see a complete unknown do the impossible (win on either pure luck or talent), just as much as we want to see a champion do his version of the impossible (by winning again and again until they become an absolute).

The two, after all … are each other’s next of kin.

At this point, the nosebleed public that sits in the back (or up high, if we’re talking the incline of the Colosseum), is usually beginning to reach the point of no return. At high altitude, air pressure is lower. Which means there’s more pressure inside your blood vessels than there is outside. With this, your blood vessels can burst and bleed. It’s no Everest, of course. But seated over a hundred feet higher than the prestigious who’s-who down below—those men (or rather: women) … would’ve felt the pressure boiling.

Further down below in the Colosseum, under the arena: gladiators and animals—equally god-given, equally godforsaken—await.

In Peter’s case, the Challenger made his first move from the nosebleed walls … by opening his mouth. And from this bed-headed, hooded, sweat-shirted kid, out came a puberty-cracked voice.

…

The reaction from the room … told me everything there is to know about the best and worst of humanity:

We like to demean someone at their most vulnerable. So as to elevate ourselves onto a position of perceived safety.

And we like to side with the clear winner. So as to preserve our own survival with the fittest.

The snickering that followed the Challenger’s stutter made it very clear:

If Peter doesn’t eat him alive, the people will.

But then Peter, walked out of the center, and did something I’ve never seen anyone done before: